Unnatural Selection

Columba livia, better known as the Common Pigeon (or back in my day, the Rock Dove), occupies an odd niche where the world of biology meets the world of human psychology. Sort of domesticated and now sort of feral, it’s sort of invasive, turning up virtually everywhere that humans have built a city or town but not moving much beyond a world defined by manmade structures. It’s sort of a pest, pooping on things and what not, but then again it lives off of human profligacy with food and thus disposes of a lot of material that would otherwise rot in the streets (or else be consumed by our other major urban symbiotes, rats and cockroaches.)

There was a time when our symbiosis was a more straightforward thing. Humans built dovecotes, which the pigeons found pleasant to nest in, and humans provided concentrations of food (grains in those days) that were convenient for the pigeons, and so the pigeons were left with plenty of leisure to make more pigeons. The humans would then eat some of the pigeons. It was a fairly simple exchange as these things go, and both pigeons and humans became major global species. As we urbanized, pigeons adapted brilliantly; today, arguably, cities and towns are their natural habitat, and they belong in cities as truly as trout belong in mountain streams and bison belong on sweeping prairies.

Nowadays, though, our relationship has become more fraught, more neurotic, burdened with a perverse hatred – pigeons are practically our collective Jungian anima, filthy because of their contact with our trash, lowly because of our own self-doubt about the rightfulness of our vast success, scorned because they’re not hiding in a mythic wilderness but right here dropping our own discarded French fries back on our shoulders. And that’s where Andrew D. Blechman’s slender but action-packed book Pigeons: The Fascinating Saga of the World’s Most Revered and Reviled Bird comes in.

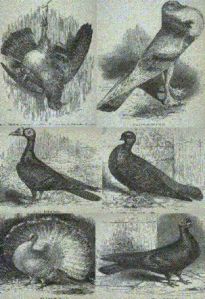

Chronicling a year of investigation into the world of all things Columba livia, Blechman comes face to face with the myriad ways that humans play out their most human impulses, for good and bad, on the bodies of these birds. Racing aficionados cater to their pigeons’ every health need – or dose them with steroids in search of the big win. Fanciers breed pigeons unable to eat on their own or fly without suffering from seizures, and then complain that street birds give their hobby a bad name. Pigeon-shooting clubs in economically depressed rural Pennsylvania torment live targets to express their futile, misguided contempt for big-city values and big-city people (often using pigeons captured from the very streets of those hated cities in the shadowy gray-market economy of pigeon poaching – and Blechman’s account of these activities cast a less sanguine light on the possibility of humane pigeon harvest that I wishfully proposed.) Lonely eccentrics take up pigeon feeding in order to feel needed and are drawn half-unwitting into realms of activism and even civil disobedience.

And, of course, some people still eat them.

By the end of the book, unsurprisingly, Blechman has been captured as well, taking up the flag of humane pigeon control after recognizing the futility of trying to poison off our own shadow side. Where pigeons are too much, he argues, it is because we need to curb waste and practice self-restraint. It seems we can look from pigeon to man, and from man to pigeon… and it is impossible to say which is which.

::

::  ::

::  ::

::  ::

::  ::

::  ::

::  ::

::  ::

::  ::

::  ::

::  ::

::

Leave a comment